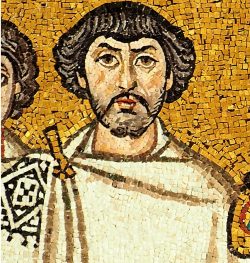

[bel-i-SAHR-ee-us]

[bel-i-SAHR-ee-us]

AD 505–565

By the year AD 476, the practical importance of the city of Rome had already seen a precipitous decline. The capital of the Roman Empire had been moved to the eastern city of Constantinople, which had been founded some 150 years prior under the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great.

By 536, the Roman Empire had held no sway over the city of Rome for 60 years. It had been conquered when a Gothic warlord took control of the Italian peninsula and proclaimed himself King of Rome. Much of the former empire had been invaded and partitioned up among various factions of barbarians. Even the lands in North Africa had been seized, no less by a tribe from snowy Scandinavia.

The Roman Empire Justinian inherited when he took the crown in Constantinople was in a state of great disarray. Religious schism threatened to pit citizens against each other; bread was in short supply; and barbarians greedily eyed the struggling empire from every corner of the world. Had this Emperor not had Belisarius by his side, it surely would have succumbed to ruin.

Belisarius distinguished himself as a dedicated servant of the Empire. He served as a bodyguard to Justinian’s father, and had been given an army to command as a result. He equipped his horsemen with heavy armor, lances, bows, and broadswords; his troops were fearsome in battle.

Belisarius distinguished himself as a dedicated servant of the Empire. He served as a bodyguard to Justinian’s father, and had been given an army to command as a result. He equipped his horsemen with heavy armor, lances, bows, and broadswords; his troops were fearsome in battle.

When Justinian came to the throne, he gave Belisarius command over an army in the Middle East, which was engaged in a war against Persia, the Empire’s greatest adversary. Belisarius managed to beat the Persians back into the boundaries of their former empire, and stopped an invasion dead in its’ tracks.

Returning to Constantinople, Belisarius pacified a rebellion which had started as an argument about chariot races. The riotous parties were threatening to depose the emperor Justinian.

Belisarius was next sent to North Africa to reclaim the fertile lands of Carthage from the Vandals, who had invaded around the same time as Rome’s capture by the Goths. The Vandals were heretics who frequently persecuted those who opposed their faith. After trapping the Vandal king Gelimer in the city of Carthage, victory fell to Belisarius, who reclaimed the land for the Roman Empire.

When Belisarius returned to Constantinople, the whole city threw a great parade in his honor, and the people’s gratitude for his military service was put on full display.

Belisarius’s triumph may have encouraged the jealousy of Justinian’s wife, Theodora. It is likely that by now Theodora would have recognized the star general’s growing popularity. That recognition, connected with her husband’s admiration for Belisarius, may have convinced her that the general’s political rise was happening all too quickly.

Justinian had aimed to restore the Roman Empire to its former glory and to wrest its rightful lands from the barbarian occupiers. Nearly all that remained now was Italy, and at its’ heart, Rome itself.

When Belisarius successfully chased the Gothic nobles out of the city of Rome, the Roman aristocrats actually offered to make Belisarius their king. Very few men in history had ever been offered such a great honor. Such a king would command much of Europe, and his fame would be forever remembered. With the Pope next door, he may even attempt to influence divine and eternal matters.

He had clearly established himself as one of the greatest military leaders the world had ever known. As a king, he would most likely bring great prosperity to his people. Yet Belisarius owed his allegiance to the Emperor, and Belisarius’s dignity prohibited him from such ambition.

While Belisarius’s refusal of the throne was a testament to the excellence of his character, the Empress Theodora was not convinced. She convinced Justinian to suspect Belisarius, and false charges of corruption were prepared against the general.

After defending Constantinople one final time (now from Bulgarian invaders from the north), Belisarius was put on trial. Ultimately the charges were dismissed, but Belisarius was disgraced, and was excluded from the Emperor’s inner circle ever afterwards. Tradition recounts a tragic fate: Belisarius was left a beggar on the streets of Constantinople—a dramatic reminder of the changeableness of political fortune. In his poem “Belisarius,” Longfellow solemnly writes:

Ah! vainest of all things

Is the gratitude of kings.